The Conspiracy Line

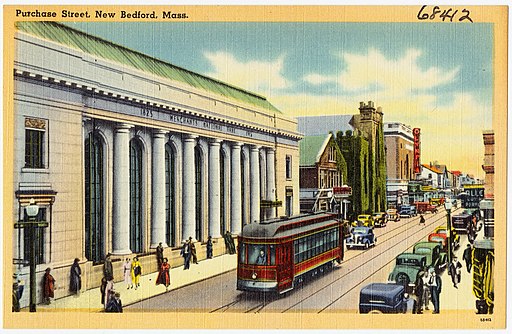

A postcard circa 1930-1945 depicts Purchase Street in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Photo from the Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection.

Comforting as it might be to blame the automobile and gasoline industries for ripping up streetcar tracks around the nation, depriving commuters of a useful commuting option, the truth in this case is that the public shoulders the greater responsibility. Individual consumers operating in their own self-interest took advantage of cheap gasoline and publicly financed road building, such as the interstate highway system started in the 1950s, to buy at least one car for every household. In most cities, taxpayers balked at public ownership of the streetcar lines, a move which would have saved many of the lines from the corporate scavenging that ultimately killed them off. In other words, GM and other auto and gas corporate interests didn’t precipitate the demise of the streetcar lines, but neither did they mourn their loss, and ultimately, of course, GM and the others profited greatly from the makeover of the American transportation system.

By the time of the 1959 release of Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, the streets of Manhattan were dominated by vehicular traffic, and mass transit options for New Yorkers were limited to subways and buses. Bernard Herrmann composed the music for the film, and Saul Bass designed the titles. The director makes his cameo appearance at the end of the title sequence.

More than a half century after streetcars were all but wiped off the map in America, they are coming back in spots like Brooklyn, driven by the desire of some people to get around town without the hassles of car ownership, the pollution of cars and buses, the blight of enormous parking lots, and the swallowing up of green spaces for more roads to alleviate the congestion on existing roads, only to have the new roads fill up as well. Streetcars powered by electricity generate pollution at a remove, to be sure, but as more power plants use renewable energy sources, that problem should lessen. Meanwhile, building out more mass transit infrastructure should take off the road some of the oversized vehicles too many Americans appear to love, and which the automobile makers and the fossil fuel industry love turning out for them since they are highly profitable. It has taken a century for Americans to learn anew the value of mass transit options like streetcars, and perhaps soon, before we reach the end of the line, gridlock on the roads will clear, and so will the air everywhere.

— Vita