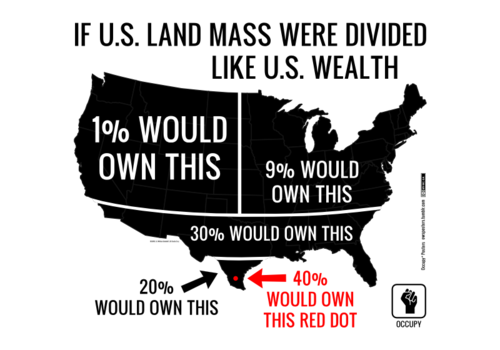

While infrastructure in the United States crumbles from neglect and is starved of public funds needed for its repair, the owners of sports teams seem to have little trouble extracting public funds for what are ultimately private facilities. Most new stadiums, arenas, and ballparks are

financed with a mixture of private and

public funds, and when a municipality refuses to throw taxpayer money into the pot, team owners threaten and cajole until they either get their way or successfully shop their team to another municipality that will contribute financing to their liking. It’s a corrupt bargain, and the benefits of a new facility for the municipality are

not nearly as great as city and team officials would conjure when they are selling the plan to taxpayers.

The Colosseum in Rome, Italy, at dusk in April 2007; photo by Diliff. The ancient Romans had their bread and circuses, too, but they built things to last.

The Colosseum in Rome, Italy, at dusk in April 2007; photo by Diliff. The ancient Romans had their bread and circuses, too, but they built things to last.The National Football League’s Raiders, after long negotiations with Oakland city officials in which the city was

prepared to bend over backwards to keep the Raiders, but refused to contribute taxpayer money for a new stadium, will move sometime within the next few years to

Las Vegas, Nevada, where city officials bent over backwards

and kicked in taxpayer money to

help build the team a new stadium. Once the new stadium is built, it won’t be named for the good people of Las Vegas, or the Raiders, or even the team’s owner,

Mark Davis, but for a corporation, in the form of advertising sold as naming rights. Tickets and concession stand items for a family of four can cost over two hundred dollars for an afternoon or evening of entertainment. Add to that a higher tax bill for years to come to pay off a luxury with nebulous benefits for the fans and the city, all of it ultimately benefiting a handful of team owners and banks, and it’s a wonder ordinary people put up with it.

But put up with it they do and, remarkably, mostly without complaint. People are so rabidly engrossed in their sports team affiliations that they allow greedy team owners and craven city officials to raid the public treasury to finance luxurious private facilities, the revenues from which will mostly go to others, and little to the taxpayers. The ordinary people

allow this while they themselves depend on roads, bridges, water supplies, and

public facilities that are neglected, derelict embarrassments. They point with a kind of perverse civic pride instead to the new, billion dollar plus stadium or arena or ballpark in their city, a facility which isn’t even their own, despite having helped pay for it. Why do they care a great deal about something that means little, when all about them

meaningful things crumble to dust?

Through the middle years of the twentieth century, Americans built the great hydroelectric dams and the major roads, including the interstate highway system we rely on still today. In those years, three of the four major sports – football, basketball, and hockey – were peripheral to the lives of most people. Only baseball took a central place, and even it wasn’t the enormous business it is today, with billions of dollars at stake. What changed all that?

Aqueduct of Segovia, Spain; photo by Bernard Gagnon.

Aqueduct of Segovia, Spain; photo by Bernard Gagnon.

Television and mass media played a part, starting in the 1950s and gathering momentum and power through subsequent decades. The NFL Super Bowl, inaugurated in 1967, is now annually the most watched television event. The next day at work, people buzz with their co-workers about the Super Bowl commercials. Another factor is the lack of civic involvement people feel, particularly in big cities. The 1950s and 1960s gave rise not only to mass media, but mass man and woman as well. Faceless cogs in the corporate machine. One person’s lonely voice doesn’t matter. You can’t fight city hall, and the Chief Executive Officer of your company is out of reach.

Remains of the Via Appia (Appian Way) in Rome, Italy, near Quarto Miglio; photo by Kleuske.

Remains of the Via Appia (Appian Way) in Rome, Italy, near Quarto Miglio; photo by Kleuske.But you can sing your team’s fight song from your seat in it’s sparkling new stadium, the stadium you may have grumbled about having to pay for, but in the end you didn’t speak up and object. It’s your team, after all, one of the few things you have left to cling to in this uncertain world. Try taking your enormous foam hand with the forefinger raised in a “We’re Number 1” gesture and going to a nearby

highway overpass, one where the concrete has crumbled away in spots, exposing the rusting reinforcing bars, and sit underneath that bridge on the sloping concrete revetment, with your enormous foam finger in your team’s colors, and start pointing out to passing motorists

the decay all around you, and see where that gets you.

― Ed.