Sped Up and Soapy

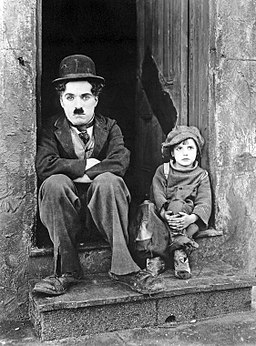

A publicity still from Charlie Chaplin’s 1921 movie The Kid, with Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Coogan. The jerky motion evident in movies of the early twentieth century was caused by shooting at a lower frame rate than the film’s projection rate. To avoid similar jerky motion when speeding up old television shows, programming providers interpolate digitally manufactured frames which unfortunately give the shows a more or less disquieting “Soap Opera Effect”. To see digital manipulation done well and not on the cheap, and for a worthy creative purpose, see Peter Jackson’s 2018 documentary using archival footage of British soldiers in World War I, They Shall Not Grow Old.

It is beyond the scope of this post to explore why the FCC doesn’t require a disclaimer for time compression of shows or how the rights agreements work between the owners of the programming and the broadcasters. Ordinarily altering a creative work without permission from the originator would be a violation of copyright. Apparently the rights agreements allow time compression, at least for some shows. Since the manipulators can time compress digitally now without noticeably raising the pitch of the actors’ voices, as on a record played at the wrong speed, the use of the technology has broadened to more shows. Some viewers may notice that the actors in late twentieth century TV shows now talk as fast as the actors in screwball comedy movies of the 1930s and ’40s. Since the actors on the TV shows didn’t intend that kind of speed, the comic timing of their speech rhythms are disrupted.

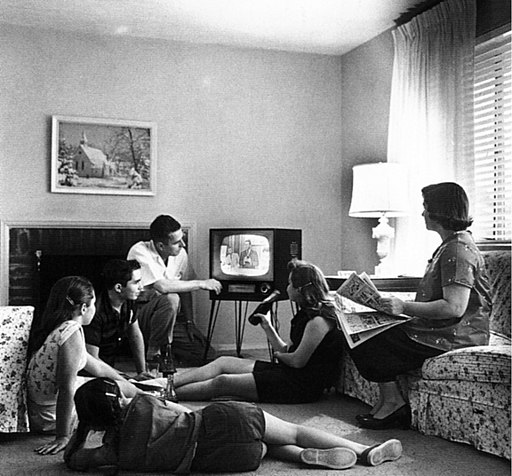

The “Soap Opera Effect”, also known as “Motion Smoothing” or something similar, comes from interpolating digitally manufactured frames to keep the sped up video from looking jerky. New television sets have the feature in their settings for those viewers who like the way it makes fast action easier to follow. The reason it can make some video look like a soap opera shot on cheap videotape equipment is because of how it shares the characteristic of a higher frame rate than programming shot on film. Many viewers don’t care for the effect and, if they know where to find the setting on their TV, turn it off. Seeing a program sped up by the provider can make viewers scratch their heads and wonder if somehow the “Motion Smoothing” setting on their TV turned itself on again. No, do not adjust your set; that unsettling look of your favorite old show is originating from the programming provider.

TBS (Turner Broadcasting System), a basic cable and satellite channel, has been a primary purveyor of sped up programming, which is ironic considering its sister channel TCM (Turner Classic Movies) is committed to presenting movies in their original form without interruption.

The Dick Van Dyke Show was a high quality program in every way, from the writing to the acting to the photography. Like many shows before and after the relatively brief popularity of shooting on videotape in the 1970s and ’80s, The Dick Van Dyke Show was shot on film. Viewed on a standard definition television set smaller than 30 inches in diagonal measurement the higher quality of film was barely discernible from videotaped programming. It is in faithful reproduction on DVD or Blu-ray formats, viewed on a high definition television set larger then 30 inches, that the photography of of old shows shot on film really shines. Viewed under such conditions, The Dick Van Dyke Show is crystal clear and not in the least bit muddy or odd looking. All that went out the window last Sunday night with MeTV’s sped up presentation of the show. It’s doubtful Mr. Reiner, by all accounts a man of integrity, and as shown in his lifetime of work a man devoted to high quality creative presentation, knew or approved of MeTV’s video corruption of his most prized creation. In all likelihood he selected the episodes for presentation and contributed some promotional bits and that was the end of his involvement. Meanwhile, let the viewer beware.

— Techly

.jpg)