Don’t Look Now

National Ice Cream Day came and went on July 16, but in case you missed celebrating it, there are still plenty of opportunities to do so even if you are only a hot weather ice cream eater. In 1984, President Reagan set aside the third Sunday of every July for celebrating the frozen treat, timing it to occur smack in the middle of summer. By 1984, the ice cream maker Ben & Jerry’s, founded by Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield in Vermont in 1978, was gaining traction regionally in New England and within a few more years would start opening ice cream parlors in the rest of the country and selling pints of its ice cream in stores nationwide.

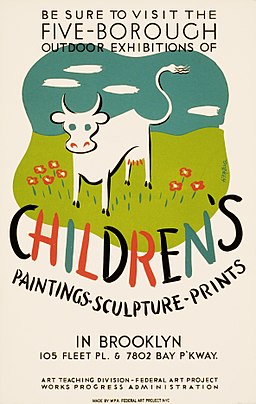

Works Progress Administration (WPA) poster, circa 1938, for the Federal Art Project, Art Teaching Division exhibition of children’s art in Brooklyn, New York, showing a child’s painting of a cow in a field.

By 2000, Ben & Jerry’s had become a publicly traded company, and when the multinational corporation Unilever made an attractive offer for the company, Mr. Cohen and Mr. Greenfield yielded to shareholders’ demands and sold the company. Since 2000, Unilever has retained the same look to the product packaging, and kept Cohen and Greenfield on the payroll as front men for the Ben & Jerry’s brand, though the two have limited input and no authority. Some loyal customers of the brand may still be unaware the company is no longer run by Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield; others may not care.

There is reason to care, however, on the part of those customers who continue buying Ben & Jerry’s ice cream in 2017 at least partly because of the reputation the former owners established in working for social justice and environmental causes. Unilever still allows their front men to put that kind of thing front and center when it comes to selling ice cream, but the multinational giant operates differently on the production end in how it treats cows and human workers who are the source if its business. To begin with, the phrase “All Natural” on the label means nothing. Ben & Jerry’s ice cream is not certified organic by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which is a label that would have some meaning to consumers concerned about healthy ingredients in their food, though it would not assure them that cows were being treated humanely in the production of milk for ice cream, or that workers were being treated well and paid fairly.

Truck from Ben & Jerry’s in Waterbury, Vermont, August 2006; photo by Hede2000.

Recent accounts of the production of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream under the stewardship of Unilever state that the company fails in all areas except continuing to charge a premium for the pint containers of its greenwashed product. People will pay a premium for high quality, to be sure, but some conscientious and health conscious individuals will also pay a premium for a product that is produced in a humane and environmentally sensitive way, among other things. Corporate executives have learned this and smelled profits in it. But hewing to those goody two-shoes methods can be expensive and appear costly on the fiscal quarter balance sheet. What to do? Produce the ice cream with low wage labor, even below minimum wage where you can get away with it, and subject the cows to factory farm confinement conditions. That keeps production costs low, while the price at the store stays high because of the goody two-shoes reputations of your front men. What’s that smell? Profits!

Cows on a farm; photo by Eric Dufresne.

Testing of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream has shown traces of Roundup in it. The amounts are within federal regulatory limits for supposedly safe consumer ingestion, but still this is Roundup (active ingredient – glyphosate) in a product that touts itself as environmentally and socially concerned. That is greenwashing. The happy cows depicted in pastures on the packaging bear no relationship to the reality of cows in confinement and fed grain from Roundup ready Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) instead of the pasture forage that is their natural diet. That is greenwashing. The company exploits human workers, too, despite the support of the founders for Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and his progressive initiatives, one of which is the Fight for $15 (raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour). That also is greenwashing, and it stinks like hypocrisy for the sake of corporate profits.

― Izzy