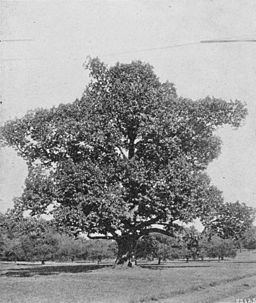

An owner of a new house on a lot where the builder

saved one or more mature trees, rather than clear-cutting the property prior to construction, may be dismayed after a few years to see some or all of those trees dying back from the tops of their crowns. The homeowner may never make the connection to soil compaction caused by heavy construction equipment running over the root zone of the trees and how that adversely affects them all the way to their tops. Typically soil compaction damage to roots of large trees takes several years to show up, and by then the realtor, the developer, and the builder have moved on, taking with them the extra money engendered by the higher value sale of a house lot with mature trees. Sometimes those parties are themselves ignorant of the horticultural damage, though they really should educate themselves.

Roots encased in compacted soil have difficulty growing through it in search of nutrients, they may have been crushed or otherwise injured during the initial period of insult, and they may rot from sitting in water because compacted soil does not drain well. After a few years of this, the constricted roots can no longer push nutrients and water to the top of a large tree, and the top dies back. Sometimes the shortened tree continues living, although it may never be as vigorous as it was prior to construction. A tree with a restricted, sickly root system is also susceptible to

toppling in a storm, the same as if its roots had been rudely shortened in a trenching operation. Suddenly that gloriously arching old oak tree providing shade and grandeur for the house 10 or 20 feet away is no longer an asset but a risk haunting the homeowner’s property. Removing the tree safely before it topples and causes catastrophic damage to life and limb is an expensive proposition.

A mother raccoon and her four kits eating cherries from a suburban backyard cherry tree at night in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Raccoons have proven highly adaptable to habitats modified by humans, moving from the wilderness to the city and everything in between. Photo by AndrewBrownsword.

A mother raccoon and her four kits eating cherries from a suburban backyard cherry tree at night in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Raccoons have proven highly adaptable to habitats modified by humans, moving from the wilderness to the city and everything in between. Photo by AndrewBrownsword.Unless the builder is serious about

protecting the roots of trees on a house lot by cordoning off an area extending at least as far the drip lines of the trees and not running heavy equipment there, excavating there, or piling soil there, then it would be better to cut the trees down and start fresh with new plantings once construction is complete. A similar policy applies to

clear-cutting trees from a woodland, though many people who are adamantly opposed to the practice may not want to hear it. As long as trees need to be cut down for timber to build houses and for pulp in the manufacture of paper products, there are only a limited number of ways of going about it. There are ways that are heedless of the surrounding environment, such as cutting trees around water bodies and on slopes without regard to controlling erosion, and there are ways which take into account the land’s recovery, such as leaving trees standing in

riparian buffer zones and leaving behind some slash – material like branches and hollow logs – to help control erosion.

A logging scene in the Ochoco Mountains, Crook County, Oregon, circa 1900. Logging without heavy mechanical equipment was lighter on the land, but little consideration was given at the time to erosion control, reforestation, or lowering the impact of road construction. This photo is part of a collection at the Bowman Historical Museum, Crook County, Oregon.

A logging scene in the Ochoco Mountains, Crook County, Oregon, circa 1900. Logging without heavy mechanical equipment was lighter on the land, but little consideration was given at the time to erosion control, reforestation, or lowering the impact of road construction. This photo is part of a collection at the Bowman Historical Museum, Crook County, Oregon.Why not leave some mature trees standing here and there throughout the logged area? For the same reason of

soil compaction that confronts the house builder who has to take extraordinary measures to sufficiently protect the roots of mature trees in order to preserve them, rather than just going through the motions. A clear-cut area often looks like a moonscape for a few years until

new growth takes over, and its appearance would no doubt be improved by a remnant of mature trees, but ultimately a sensitivity about appearances may not prove to be in the best interest of the trees themselves. Ultimately where logging has to be done to provide the paper products and

building materials nearly everyone uses, it may be best to get in and get out, employing best practices to control erosion, perhaps

repairing soil compaction where possible, and then either replanting or allowing the land to regenerate new growth on its own. After that, leave the land alone for a generation or more. Hand-wringing about the removal of trees may be a satisfying demonstration of environmental sensitivity, but unless it is accompanied by an understanding of best practices in pursuit of necessary economic activity, it is best not undertaken by those living in wood houses.

— Izzy