The Ginger Kick

There are some cocktails gaining popularity the past few years which get a kick from ginger beer, among them the vodka-based Moscow Mule and the rum-based Dark ‘n’ Stormy. Ginger beer doesn’t deliver its kick by way of alcohol, since nearly all ginger beer available commercially now is non-alcoholic, but from the spiciness of ginger, which is more pronounced in ginger beer than in its tamer cousin, ginger ale. People almost never confuse ginger ale with any kind of alcoholic brew, probably because of their long familiarity with the product. They know it’s just soda pop, the one they often drink to settle their stomach when they’re not well.

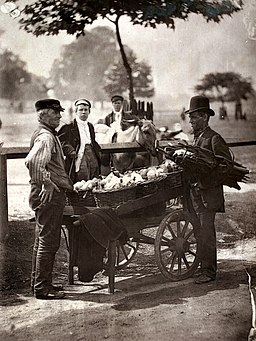

From Volume 1 of Street Life in London, published in 1877, with photographs by John Thomson and articles by Adolphe Smith. The man on the left is a street vendor peddling ginger beer, among other items. The man on the right is a “mush faker”, or umbrella mender.

Ironically, the ingredients in ginger that people count on for settling their stomach, the gingerols, are present in the most popular ginger ales only in vanishingly small homeopathic quantities. Stronger flavored ginger ales, and especially ginger beers, are more likely to have gingerols in quantities sufficient for an effective dose. Whatever people are gaining by drinking most ginger ales medicinally, they are getting it from some factor other than the amount of actual ginger in the drink. This is a turnabout from where things stood between ginger ale and ginger beer over on hundred years ago.

Up until the late nineteenth century, there was only ginger beer, all of it alcoholic to some extent, and especially popular for centuries in England after that country had secured supplies of ginger, a subtropical plant. When pharmacists started producing soft drinks in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, ostensibly for the medicinal benefits, one of the first flavors they produced was ginger ale, a toned down version of ginger beer. Ginger ale really took off in popularity during Prohibition, when people naturally drank quite a lot of spirits and they discovered what a wonderful mixer ginger ale made. In the United States at least, ginger beer was all but forgotten.

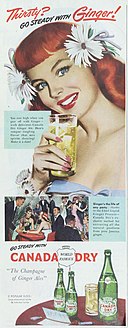

A 1948 advertisement for Canada Dry Ginger Ale in The Ladies’ Home Journal. The nightclub scene depicted in the inset emphasizes the popular use of the product as a mixer for cocktails.

Consumers have rediscovered ginger beer in the last ten to twenty years as they have also opened themselves up to alternatives to other mass produced products like the sodas and beers of multi-national corporations. Ginger has also generated interest as an anti-inflammatory home remedy, for treating arthritis and, again, for digestive complaints. The difference now is that many consumers recognize the amount of ginger in the typical mass market ginger ale is not enough to be medicinally worthwhile, homeopaths excepted. This has driven some consumers to the niche market of ginger beers, with their higher amounts of actual ginger, sometimes mixed with other spices, and consequently stronger flavors. Along the way, the drinkers of alcohol among them, unmoved by the lack of alcohol in their newly discovered ginger drink of choice, have found that mixing it in cocktails and punches which would normally call for ginger ale can deliver a more flavorful kick than ginger ale, and maybe a healthier benefit, which if negligible when mixed with alcohol, could perhaps come into play the next day if the drinker is out of sorts.

— Izzy

— Izzy