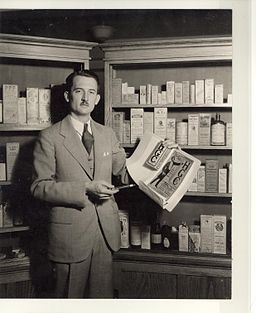

A Dose of Gobbledygook

George Larrick was the last investigator to rise through the ranks to become Commissioner (1954-1965) of the Food and Drug Administration. Inspector Larrick assembled an exhibit of dubious and even dangerous food and drug products, dubbed by reporters an “American Chamber of Horrors”, which effectively documented the need for what became the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Photo from the Food and Drug Administration.

What has changed since then has been the increasing average age of the population and the consequent increase in demand for medicines to treat their growing health complaints. Drug manufacturers are also not above boosting demand with lengthy and frequently repeated television commercials urging prospective users to pressure their doctors into prescribing the advertised medicine. They cover the other end as well by sponsoring junkets and giveaways for doctors, nudging them toward prescribing the latest drug they have developed.

A most excellent reading by Irene Worth and John Gielgud in 1983 of T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. The entire book is presented in this video, but the part that concerns us here is the first poem, “The Naming of Cats”, which proceeds up to the 1:45 mark.

It’s a high stakes game for pharmaceutical companies that have spent millions of dollars on research and development for a drug, and then millions more on shepherding it through FDA approval, and finally marketing it. Notice how television drug ads are 60 seconds long instead of the usual 30 seconds, and how often they are repeated, particularly during the day when their target audience of older people are presumably at home watching. There’s gold in them thar hills of retirement, and pharmaceutical companies mean to get their share. Whether the residents of the golden hills are better off with the latest heavily advertised gobbledygook drug or something else, or with nothing at all, is up to them and not to marketers, no matter how warm and fuzzy the television ads portray their lives can be, to paraphrase the Rolling Stones “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”, an old song the human targets of drug ads might still remember well.

— Ed.