In a 2019 article for the British Broadcasting Corporation, Sharon George and Dierdre McKay wrote, “If you only listen to a track a couple of times, then streaming is the best option. If you listen repeatedly, a physical copy is best . . . ” They were referring to the comparative environmental costs of listening to music either over the internet or reproduced on an electronic device. They could just as well have been giving excellent advice on the best strategy for enjoying all types of entertainment media in the digital age.

Owning physical copies only of favorite movies, television shows, books, and music, while streaming more transitory entertainments, is not only better for the environment, but better in all sorts of other ways. Buying an entertainment you may enjoy only once or twice is expensive and takes up shelf space in the home. Streaming choices are often limited to the most popular or the newest entertainments, leaving outright purchase from a vendor or borrowing from a library as the only options for enjoying more obscure, less widely popular works.

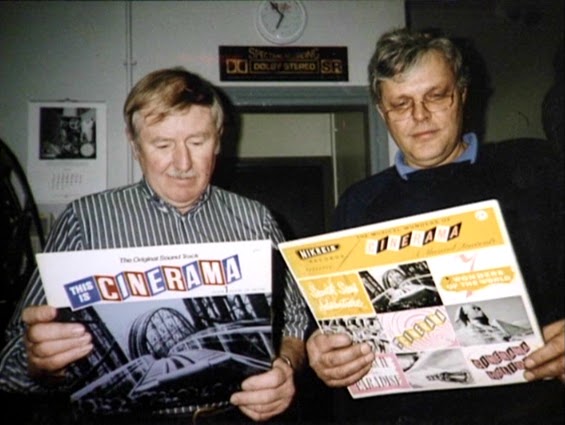

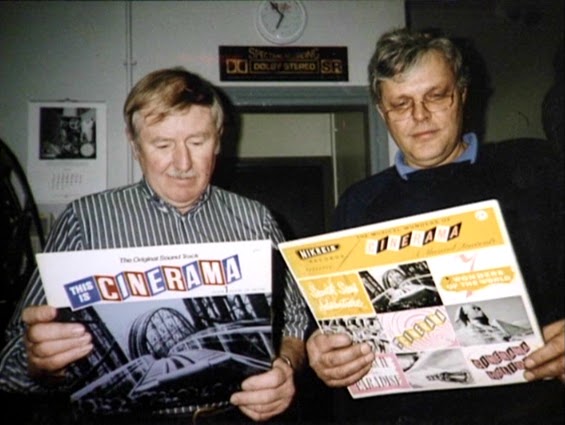

Cinerama historians John Harvey and Willem Bouwmeester photographed in 1987 examining the back covers of vinyl record albums devoted to music used in Cinerama productions. After many years years researching all things Cinerama, they eventually collaborated on the Cinerama installation in Bradford, England, in 1993. Photo by LarryNitrate2Cinerama.

Cinerama historians John Harvey and Willem Bouwmeester photographed in 1987 examining the back covers of vinyl record albums devoted to music used in Cinerama productions. After many years years researching all things Cinerama, they eventually collaborated on the Cinerama installation in Bradford, England, in 1993. Photo by LarryNitrate2Cinerama.There are indeed thousands of movies and television shows available on the streaming services, but a close examination reveals that the majority of those on the advertisement supported services are public domain properties that will be familiar to anyone who has rooted through the bargain DVD and Blu-ray bins at big box stores. The subscription streaming services are meanwhile moving toward

a vertical integration model reminiscent of the Hollywood studios in the days when they owned production and distribution from top to bottom.

If you want to watch the latest Star Wars franchise release and you missed it during it’s brief theatrical release, then you must subscribe to Disney’s streaming service or go without. Some films these days don’t get a theatrical release at all. Another option is to buy the physical media if and when it becomes available. But in that case you would still want to watch the movie first to be sure it’s worth buying. It’s likely there will be always be a hardware means of playing back most electronic media, the trick is in guessing correctly which ones will stand the test of time.

30 years ago, many people thought vinyl record albums were all but dead. Only a tiny niche market of record collectors and audiophiles would continue to have need of record players and record player parts. Few people in 1991 would have guessed that by 2021

sales and production of vinyl records would have reemerged from the dustbin, while compact discs and players, for

a brief period the predominant music delivery system on the market, would be

overtaken first by digital downloads, and then by streaming music services.

A similar dynamic appears to be at play in the visual media market of movies and television shows. Despite the close resemblance of

DVDs and Blu-ray discs to music compact discs, they are more comparable to vinyl records in quality of reproduction and in the way consumers use them. Blu-ray discs in particular are attractive items for ownership by collectors and cinephiles due to the

outstanding quality of their video and audio reproduction, which can often outstrip what’s available for the same title on a streaming service.

Despite big manufacturers like Samsung discontinuing Blu-ray player production a few years ago because they noted the decline in the market to niche status, and similarly Warner Brothers recently moving toward ceasing production of discs, there will always be a demand for new Blu-ray players and new Blu-ray discs, however much the market shrinks for now. Just ask the manufacturers of vinyl records and the turntables needed to play them.

— Techly