Many More Than 57 Varieties

The Heinz “57 Varieties” slogan is well known but not well understood, which is just as well for a slogan, especially since it doesn’t mean anything particularly. The slogan was meant to evoke in the consumer’s mind a satisfied feeling that the H.J. Heinz Company offered them a lot of products, in great variety. People seem to want that feeling, and corporate America has been willing to oblige them.

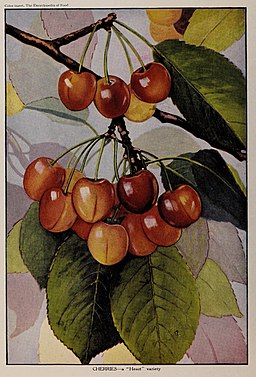

An illustration of Cherries of the “Heart” variety from The Encyclopedia of Food, a 1923 book by Artemas Ward. In this case, the reason for enclosing the word “Heart” in double quotation marks has to do with reference to the shape of the fruit, not to a cultivar, in which case only single quotation marks would be the practice. Botanical nomenclature can be confusing.

Horticultural companies and plant breeders have tried to fulfill that desire as well, for a variety of reasons, from interest in making a profit from patented cultivars to academic interest in genetics and in improving plant varieties. To speak of cultivars and varieties is not to use two words for the same thing, since varieties are naturally occurring while cultivated varieties are cultivars, a portmanteau word. To create cultivars, however, companies and breeders often take advantage of naturally occurring varieties.

A cultivar is not always an improvement in the long run, as shown by rose bushes which cannot stay healthy without human intervention in the form of applying copious amounts of pesticides and fungicides, some of them environmentally costly, as well as expensive to purchase. It has been short-sighted to breed roses for traits like flower shape and fullness and repeat blooming at the expense of plant vigor. it has been unforgivable to lose fragrance in many rose cultivars along the path to achieving other less salient rose traits. What is a rose, after all?

Fortunately, most plant geneticists are not like Dr. Alphonse Mephesto, a fictional scientist who produced useless anomalies for the gratification of his own ego and morbid curiosity on the animated television show South Park. The Green Revolution of the 1950s through the 1960s was fueled by botanists in academia and the private sector working hard to forestall what they perceived as the imminent possibility of widespread starvation as worldwide population exploded.

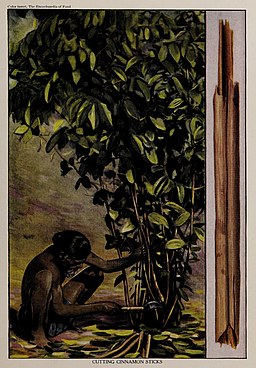

Cutting cinnamon sticks, another illustration from The Encyclopedia of Food, by Artemas Ward. Cinnamon identification has been confusing over the years, with several closely related plants being called cinnamon in the spice trade.

The Green Revolution scientists and horticultural companies did important work, even though the problem with alleviating hunger has rarely ever been horticultural primarily, but a problem of human greed and lack of empathy in the distribution of food and other resources. Abundant food rots in granaries and warehouses on one half of the world while the other half starves, often for no reason other than to enrich already wealthy speculators. It’s good to have a wealth of choices and to be able to choose a healthier plant over a weaker one, but what really needs changing are our choices about what to do with what we already have.

— Izzy

— Izzy