It Grows without Spraying

A jury at San Francisco’s Superior Court of California has awarded school groundskeeper Dewayne Johnson $289 million in damages in his lawsuit against Monsanto, maker of the glyphosate herbicide Roundup. Mr. Johnson has a form of cancer known as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and it was his contention that the herbicides he used in the course of his groundskeeping work caused his illness, which his doctors have claimed will likely kill him by 2020. Hundreds of potential litigants around the country have been awaiting the verdict in this case against Monsanto, and now it promises to be the first of many cases.

Migrant laborers weeding sugar beets near Fort Collins, Colorado, in 1972. Photo by Bill Gillette for the EPA is currently in the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Chemical herbicides other than Roundup were in use at that time, though all presented health problems to farm workers and to consumers. Roundup quickly overtook the chemical alternatives because Monsanto represented it, whether honestly or dishonestly, as the least toxic of all the herbicides, and it overtook manual and mechanical means of weeding because of its relative cheapness and because it reduced the need for backbreaking drudgery.

Monsanto has long been playing fast and loose with scientific findings about the possible carcinogenic effects of glyphosate, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) currently sides with Monsanto in its claim that there is no conclusive evidence about the herbicide’s potential to cause cancer. In Europe, where Monsanto has exerted slightly less influence than in the United States, scientific papers have come out in the last ten years establishing the link between glyphosate and cancer. Since Bayer, a German company, acquired Monsanto in 2016 it remains to be seen if European scientists will be muzzled and co-opted like some of their American colleagues.

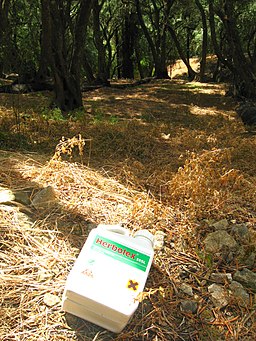

The intensive use of glyphosate herbicide to remove all ground vegetation in olive groves on Corfu, a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, is evidenced by the large number of discarded chemical containers in its countryside. Photo by Parkywiki.

The scope of global agribusiness sales and practices that is put at risk by the verdict in Johnson v. Monsanto is enormous. From the discovery of glyphosate in 1970 by Monsanto chemist John E. Franz to today, the use of the herbicide has grown to the preeminent place in the chemical arsenal of farmers around the world and has spawned the research into genetically modified, or Roundup Ready, crops such as corn, cotton, and soybeans. There are trillions of dollars at stake, and Monsanto and its parent company, Bayer, will certainly use all their vast resources of money and lawyers to fight the lawsuits to come.

Because scientists have found traces of glyphosate in the bodies of most people they have examined in America for the chemical over the past 20 years as foods from Roundup Ready corn and soybeans spread throughout the marketplace, they have inferred it’s presence is probably widespread in the general population. That means there are potentially thousands of lawsuits in the works. Like the tobacco companies before them and the fossil fuel industry currently, agribusiness giants will no doubt fight adverse scientific findings about their products no matter how overwhelming the evidence against them, sowing doubt among the populace and working the referees in the government.

— Izzy

— Izzy