Name Calling

There are thousands of colorful place names in the United States, and some go beyond colorful to denigrate one group of people or another, though it’s questionable whether all of them were intended to do so originally. Ideas of what’s acceptable in society change, and place names don’t have to be unchangeable. The history of a place can be kept alive in books and museums; it’s not necessary that a name given it long ago out of ignorance, malice, or a misguided sense of humor be kept despite its deleterious effect on people of today.

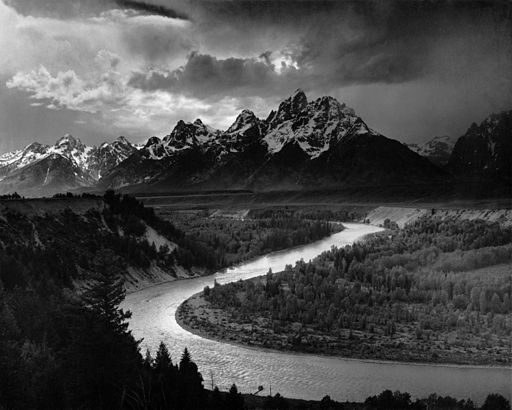

Ansel Adams took this photograph, The Tetons and the Snake River, in 1942, at Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, while he was employed by the U.S. government. Photo from the National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the National Park Service.

The best personal way to remember a place may be to have memories of it, and for that purpose the name of the place can be anything. It is in describing the place to others, in pointing it out to them on a map, that it requires an official name, of course. So it is in social intercourse that a place name becomes relevant, and when relating to others it helps not to insult them at the very first, if at all.

A 2004 view of the John Moulton Barn on Mormon Row at the base of the Grand Tetons, Wyoming. Photo by Jon Sullivan.

Unless that’s the point – to exclude some others, possibly, and to announce that the name of this particular place is only understandable within the communications of a certain group, and it is not meant for everyone. In that case, it’s name might as well be “Keep Out”. A better name, one which would eventually improve the outlook of a place’s inhabitants besides giving encouragement to visitors, would be “Welcome”.

― Izzy

― Izzy