Marking Time

Alice sighed wearily. “I think you might do something better with the time,” she said, “than wasting it in asking riddles that have no answers.”

“If you knew Time as well as I do,” said the Hatter, “you wouldn’t talk about wasting it. It’s him.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” said Alice.

“Of course you don’t!” the Hatter said, tossing his head contemptuously. “I dare say you never even spoke to Time!”

“Perhaps not,” Alice cautiously replied; “but I know I have to beat time when I learn music.”

“Ah! That accounts for it,” said the Hatter. “He won’t stand beating. Now, if you only kept on good terms with him, he’d do almost anything you liked with the clock.”

— from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll.

Did the new decade begin a few days ago, or more than a year ago? Sticklers for numerical accuracy would say the 2020s began on January 1, 2021. But for most people, referring to the decade in the course of everyday conversation, it makes more sense to speak of January 1, 2020, through December 31, 2029, as the 2020s. It’s awkward to claim the year 2020 is not part of the 2020s, while the year 2030 is the last year of the decade. This enumeration is technically correct, but it requires a tedious explanation every time it’s dragged out and it smacks of pedantry.

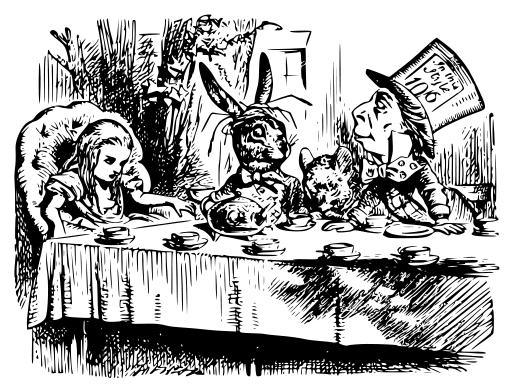

Illustration by John Tenniel (1820-1914) for the 1865 edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. At the table for the Tea Party are Alice, the March Hare, the Dormouse, and the Mad Hatter.

So yes, there are discrepancies. Not that they matter much to most people: it’s not as if there is real money at stake from missing appointments and having communication failures. Those dates and times have a finer point to them than the decades that roll by, as Alice knew when she disputed with the Mad Hatter the necessity of broad markings of time on a watch. A watch is for marking seconds, minutes, and hours, and a calendar is for marking days, weeks, and months. Nature, however, continues to mark the time for all on the broadest possible scale and, for those who pay attention, on the smallest scale imaginable.

David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash perform “Wasted on the Way”, a song written by Mr. Nash.

Stroll through Nature and you will note that Time is subjective, and different creatures and plants exist on different scales. A hummingbird lives at a pace unimaginably fast to us, but of course the hummingbird is adjusted to its own timescale. To a hummingbird, we must appear to be moving in slow motion. The opposite may be the case for a giant redwood tree, if it can be said to have perceptions. To the redwood, we are perhaps like hummingbirds. We lose sight of Nature’s timekeeping, and instead give undue importance to our own arbitrary social constructs for timekeeping. The middle ground from seconds to years suits us well on the timescale of our lifespans, which are not as short as that of hummingbirds nor as long as that of giant redwood trees. Take the time to stroll through Nature, and leave the watch behind.

— Izzy