The measles outbreak in Clark County, in the southwestern corner of the state of Washington, across the Columbia River from Portland, Oregon, has brought

national attention to the beliefs of people who do not get some or all vaccinations for one reason or another, because vaccination rates in

Clark County are far below the national average. The term many have come to apply to these people is “anti-vaxxer”, though it

unfairly lumps everyone together, including people who are less against vaccines as they are for personal liberty, or who object on religious grounds. Since vaccination is

a public health issue, however, the reasons for not getting vaccinated do not matter as much as the effects.

The history of the differing reasons for vaccine opposition goes back to the introduction of the smallpox vaccine,

primarily by Edward Jenner, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in England. The idea that to combat a disease a person should voluntarily introduce a weakened form of it into his or her body ran counter to reason. Vaccination methods of the time were

far cruder than today, and since sterilization of wounds and bandages were little understood, infection often followed upon vaccination. The alternative was death or disfigurement from a full force smallpox infestation, and some religious folks actually expressed preference for that because it was “God’s will.”

In Merawi, Ethiopia, a mother holds her nine month old child in preparation for a measles vaccination. One in ten children across Ethiopia do not live to see their fifth birthday, with many dying of preventable diseases like measles, pneumonia, malaria, and diarrhea. British aid has helped double immunization rates across Ethiopia in recent years by funding medicines, equipment, and training for doctors and nurses. Photo by Pete Lewis for the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID).

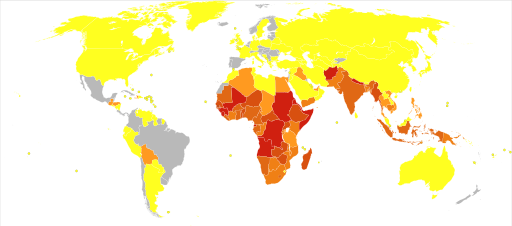

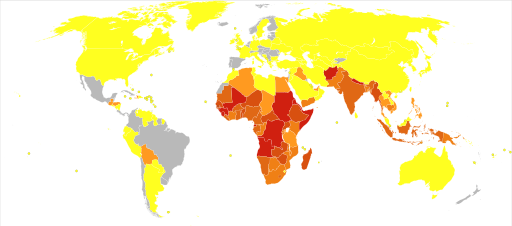

In Merawi, Ethiopia, a mother holds her nine month old child in preparation for a measles vaccination. One in ten children across Ethiopia do not live to see their fifth birthday, with many dying of preventable diseases like measles, pneumonia, malaria, and diarrhea. British aid has helped double immunization rates across Ethiopia in recent years by funding medicines, equipment, and training for doctors and nurses. Photo by Pete Lewis for the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID). World Health Organization (WHO) 2012 estimated deaths due to measles per million persons, with bright yellow at 0, dark red at 74-850, and shades of ocher from light to dark ranging from 1-73. Gray areas indicate statistics not available. Map by Chris55.

World Health Organization (WHO) 2012 estimated deaths due to measles per million persons, with bright yellow at 0, dark red at 74-850, and shades of ocher from light to dark ranging from 1-73. Gray areas indicate statistics not available. Map by Chris55.

Those who didn’t object to vaccination on grounds of cutting into a healthy body and introducing a light case of the disease or a bad case of infection, or of meddling in God’s will, objected to the perceived unnaturalness of the procedure since the vaccine ultimately came from cows infected with cowpox. To those people, introduction into the human body of something from an animal was unwholesome, even dangerous. Never mind that people do the same thing all the time when they eat meat, presumably from animals and not from other people, without the ill effects these folks foresaw, such as taking on the traits of animal whose parts were introduced directly into human flesh. On the other hand, perhaps they were taking the dictum “you are what you eat” to a logical extreme somehow unimpeded by the process of digestion.

It is probably best not to overload these viewpoints with the rigors of logic. People have their opinions, and they often do not bother to make the distinction between opinions and facts. The fact is that through vaccination programs, smallpox has been eradicated worldwide since the middle of the twentieth century, roughly 150 years after introduction of the vaccine. Similarly, measles in the United States disappeared around the turn of this century after nearly 50 years of vaccinations. About the time measles was going away in this country, in 1998 a doctor in England,

Andrew Wakefield, published a report in the English medical journal

The Lancet linking the

MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) vaccine to autism and bowel disorders, and though the findings in the report and Dr. Wakefield himself were soon

repudiated by the majority of other medical professionals, some anti-vaxxers latched onto the link with autism and have been

running with it ever since, regardless of the lack of evidence to support the link.

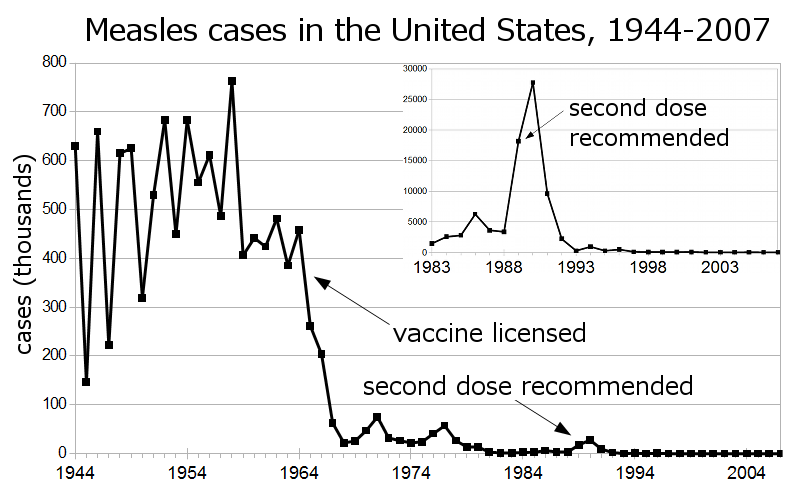

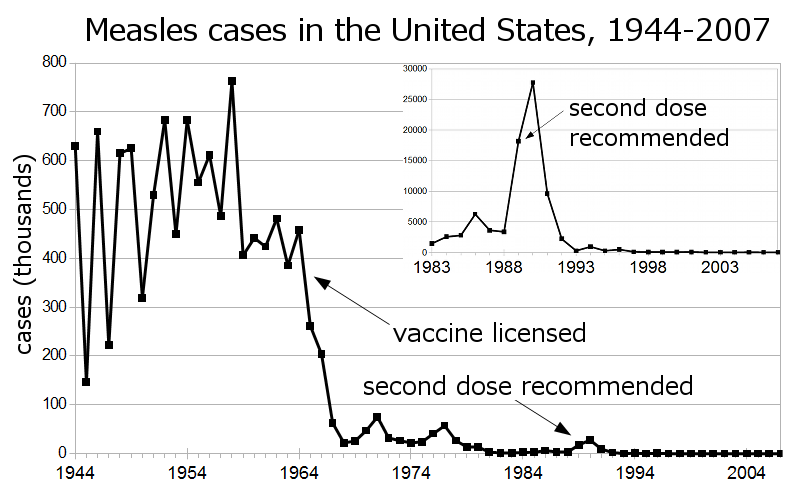

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statistics on U.S. measles cases (not deaths). Chart by 2over0.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statistics on U.S. measles cases (not deaths). Chart by 2over0.The problem with anti-vaxxers of one stripe or another running with opinions mistaken for their own version of the facts is that vaccinations are needed most by vulnerable populations such as the very young, the very old, and people with suppressed immune systems. Infants cannot be vaccinated against measles at all. Many of these vulnerable people are in the position of having decisions made for them by responsible adults. In the case of children, that would be their parents, who of course have

the best interest of their children at heart. The difficult point to get across to those parents is that in a public health issue involving communicable diseases, their decision not to vaccinate their children affects not only their children, but those other most vulnerable members of the greater society as well. Public health is a commons, shared by all, like clean water and clean air, and the

tragedy of the commons is that a relatively few people making selfish decisions based on ill-informed opinions can have a ripple effect on everyone else. Personal liberty is a fine and noble ideal, but when it leads to poisoning of the commons then quarantine is the only option, either self-imposed or involuntary.

— Vita