We evolved to chase down game using a tactic known as perseverance hunting. Most land mammals evolved to run fast for short stretches, while we became

uniquely adapted for endurance running. Perseverance – or persistence – hunting involves wearing down prey animals until they overheat and are no longer capable of evasion, or running them into traps of one sort or another from which the animals are too weary and bewildered to escape.

To keep ourselves from overheating during the long chase, we evolved to sweat through our skin, a process which carries heat away through evaporation. Sweating as a means of cooling is most efficient in dry air.

In humid air our sweat does not evaporate readily, and consequently we seek alternative methods of cooling, such as finding shade or a pool or spray of cool water.

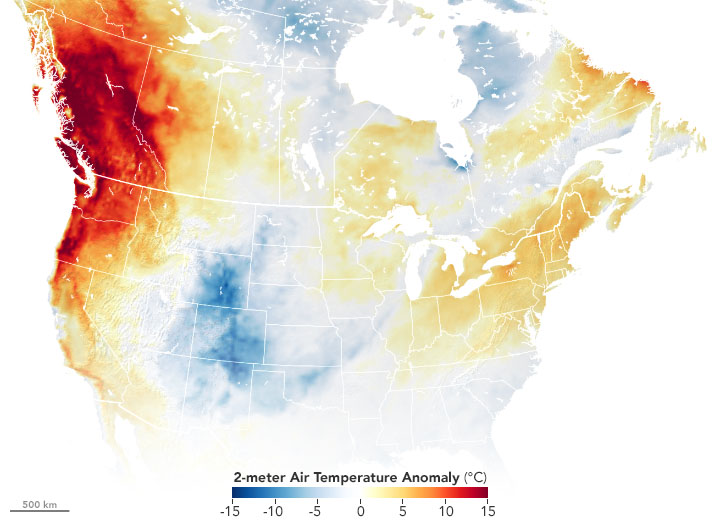

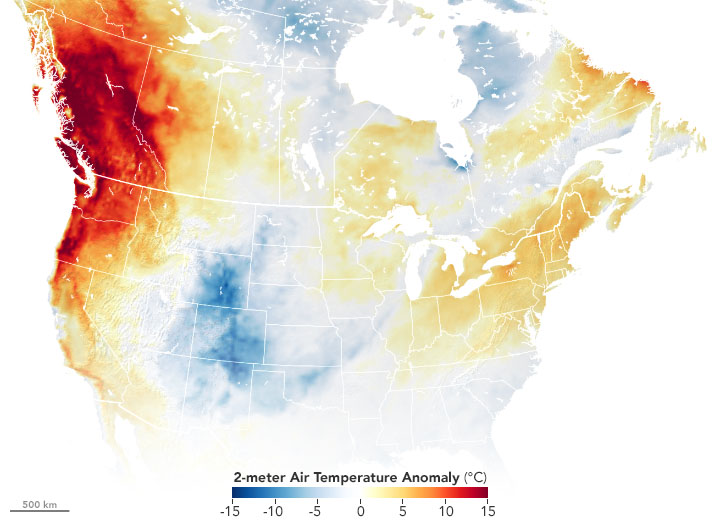

During the 2021 western North America heat wave, data from the NASA Earth Observatory shows temperature anomalies on June 27, 2021 as compared to the June 27 average from 2014 through 2020. Map compiled by Joshua Stevens.

During the 2021 western North America heat wave, data from the NASA Earth Observatory shows temperature anomalies on June 27, 2021 as compared to the June 27 average from 2014 through 2020. Map compiled by Joshua Stevens.All of this hunting and running and sweating expends energy, which works against our other evolved trait of conserving energy. We call expending energy “work”, and the conservation of energy “leisure” or “relaxation”, and sometimes “laziness”. We have attached

attitudes to these words, and the attitudes follow the words as we adapt them to evolving circumstances.

Runners participating in the June 5, 2010 Marine Corps’ Camp Pendleton Mud Run are cooled off by fire hoses at Lake O’Neill. During the event, runners traversed various obstacles, including a 30 foot long mud pit.

Runners participating in the June 5, 2010 Marine Corps’ Camp Pendleton Mud Run are cooled off by fire hoses at Lake O’Neill. During the event, runners traversed various obstacles, including a 30 foot long mud pit.“Work” is typically not fun, and “laziness” is usually not productive. At least that is how many of us teach ourselves and our children to think of those activities or conditions. These ideas carry over to

our feelings about exercise, especially when we undertake it primarily to fend off the detrimental health effects of a sedentary lifestyle. In that case,

exercise is a chore, it is “work”. “Relaxation”, on the other hand, is pleasant. “Leisure” can be downright fun. Exercise can only be fun when it is the byproduct of play, as it is in sports.

Interestingly, we consider work virtuous, and leisure is something we gain in reward for work. Work first, play second. This would appear to make sense on the grounds that hunting procures calories to sustain ourselves. No work, no food. But that’s not entirely accurate. Hunting and running and sweating expends an awful lot of energy in the pursuit of gaining energy. Meanwhile, plants don’t run away. There is still work involved in obtaining calories from plants, just not as much as in bringing home a steak dinner. Maybe a life of gathering plants for food involves a bit more leisure than hunting down animals in order to gnaw on their flesh.

Unless through greed and a desire for an easy lifestyle for themselves the idea of producing a surplus of food is introduced by an aggressive minority of people. With control of the surplus comes wealth and control of the majority population. Some of the hunters, the most aggressive ones, set themselves up as the dominant members of the group, the tribe, the clan, as if it were in the natural way of things. Through it all winds the twin salient features of our species: Our near constant need for water, and

our large brains.

Swimmers cool off in the Kuang Si waterfall and pool in Laos on August 4, 2011. Photo by McKay Savage.

Swimmers cool off in the Kuang Si waterfall and pool in Laos on August 4, 2011. Photo by McKay Savage.We sweat because of muscle activity that generates heat, and to replace that sweat we require continuous replenishment by drinking water. Our large brains also generate heat, and they too need water regularly to remain productive. A prominent symptom of dehydration is

impaired brain function, the same condition that affects animals run down in a hunt to the point of overheating. Our need for regular access to healthy drinking water makes us vulnerable to control by people who take it over. Who controls access to water, controls the populace.

Overlooking the Rogue River Valley in southwestern Oregon on September 20, 2012. Photo courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management.

Overlooking the Rogue River Valley in southwestern Oregon on September 20, 2012. Photo courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management.

Having large brains enabled us to develop tools for successful hunting, and eventually tools for agriculture and animal husbandry that produced a surplus which allowed a minority to amass wealth and to exert control over the majority and their most vital resource, water. We were told that productive work generated from the sweat of our brows was good and honorable, the better to produce wealth and power for the minority. And somewhere along the line the conditions of work for the majority began to flip from sweaty, manual labor to sedentary, brainy employments. To keep their muscles from atrophying, they began to exercise, and it seemed like work, manual work, and exercise in service to that goal became a virtuous duty, all while their brains continued to

proclaim their thirst.

— Izzy

_flowers.jpg)