There Are No Easy Answers

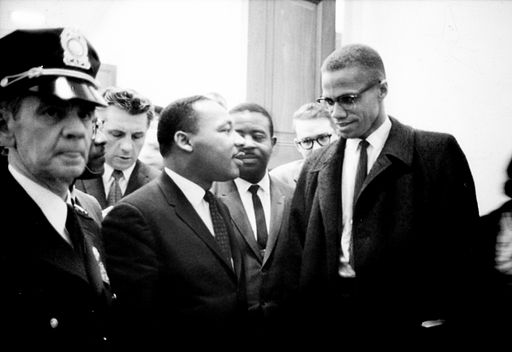

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X waiting for a press conference to begin in March 1964. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko for U.S. News & World Report, now in a collection at the Library of Congress.

Ossie Davis as Da Mayor has a confrontation with some youths on the street in Do the Right Thing. Warning: foul language.

30 years later Do the Right Thing stays with people who view it now for the first time as much as it did with people who saw it then, prompting the same questions in their minds. A few years before Mr. Lee made the film, there was the racially charged incident at Howard Beach in the New York City borough of Queens, an incident which informed the events in Do the Right Thing. Two years after the movie came out, there was the police beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles, and despite the incident being filmed by a bystander, showing the excessive use of force by the police, the cops were subsequently cleared in court, leading to riots in black neighborhoods. There has been no end of ugly, often fatal, incidents in America like those portrayed in the movie, and they just keep coming, like waves pounding the shore. The observations Spike Lee made in Do the Right Thing about race relations in America are still relevant today; the question remains – is anybody listening well enough to change things?

— Vita

“I just want to say – you know – can we all get along? Can we, can we get along? Can we stop making it horrible for the older people and the kids?”

— Rodney King, speaking on television in relation to the riots in Los Angeles on May 1, 1992, after a jury acquitted the police who beat him the year before.